Blue Archive’s Essence and Yang’s True Passion for Jokes

—Up until this point, we’ve discussed how Blue Archive was created. Now I would like to dig deeper into how you left your mark on this work, but what exactly do you think it was that allowed you to achieve Blue Archive?

Yang:

The humor. In other words, the jokes. Jokes are my strong point.

Jokes have the most intuitive effect, and they attract the player’s interest and curiosity. Beautiful, dainty girls suddenly become macho or start robbing banks in masks… These outrageous events take people by surprise and open their hearts to the game’s world.

Jokes have the effect of keeping context simple. Content nowadays has become increasingly quick and short and is consumed more intuitively. We have a responsibility to constantly think of storytelling methods that conform to the times. We must continue to improve our methods of expression to convey things to others.

Saito:

As an indie game producer myself, I know full-well the importance of jokes in games. Even so, when you start to actually think of how you can incorporate jokes in a game, it’s pretty challenging. Do you have any tricks for depicting jokes?

Yang:

I can’t teach you any tricks. It’s simply not possible. Jokes are all about talent. Those skilled at making jokes are like that from the start, and those who aren’t cannot improve even if they try. So I do not teach the writers on my team how to make jokes.

The most I can do from a manager’s standpoint is to give writers skilled at jokes opportunities that fit with the quality of their jokes.

Saito:

So innate sense of humor is important especially for a genre that appeals to intuition and human nature.

Yang:

And because it is an intuitive field, it tends to be taken too lightly.

There is this story about the Weekly Shonen Jump magazine a while back. In popularity polls among readers, the more serious works ranked higher, with the comedy manga not getting a lot of votes. However, contrary to the polls, sales of comedy manga were high. That’s because there is this aspect to comedy manga where it’s hard to say honestly that you like it despite everyone reading it. Comedy manga that is read and then quickly discarded is often looked down on compared to other genres.

Therefore, to implement a joke as part of the story, you must refine your strategy. However, jokes shouldn’t just be told. They need to be simultaneously serious and profound and in some way add value.

Gintama is a good example when it comes to Japanese manga. At its base, it is a childish comedy manga, but it can sometimes be serious and cool. The serious parts and the comedic parts are separated and sometimes blended to maintain just the right balance. One Piece also does a superb job of balancing comedy with seriousness.

Although I used jokes as a hook to attract the attention of users, I also aspire to be creative. By adding a certain refinement to the light-heartedness, I add depth to the story.

Saito:

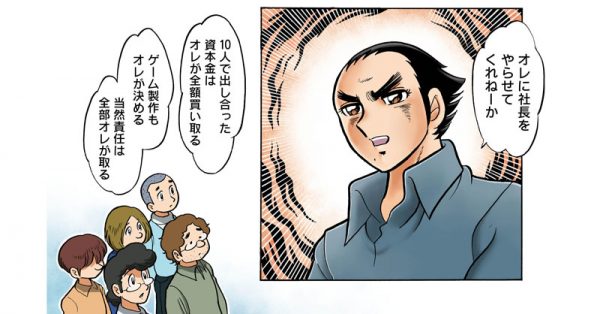

A good example is the dialogue between Shiroko and Shiroko Terror during the bank heist.

Yang:

I’m happy to hear that you think so.

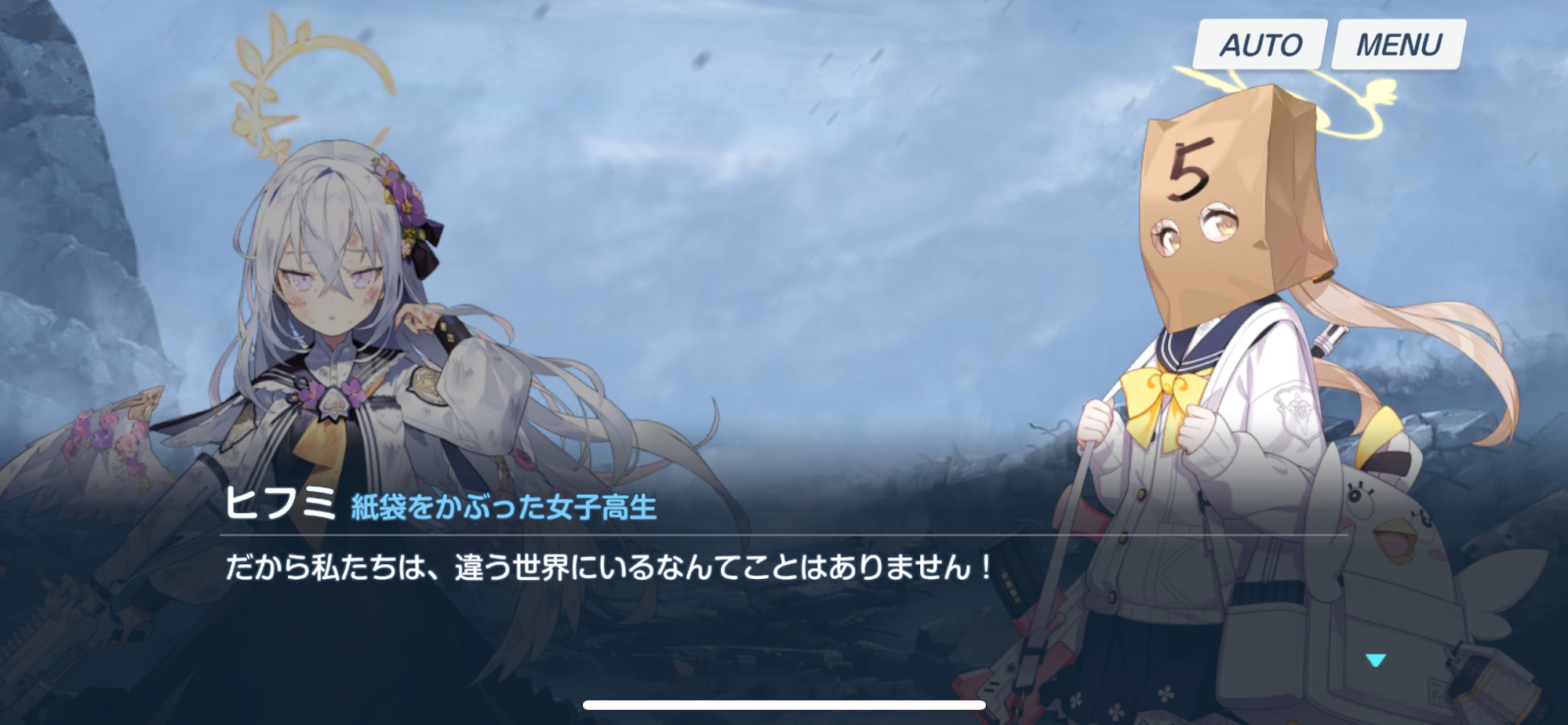

My goal is to convey emotions that are difficult to define through the story. For instance, in Eden Treaty when Hifumi wears the paper bag, Hifumi tells Azusa that she’s in the same world as her.

—It may seem like an absurd scene when you see it, but to players actually playing the game, it both moves them and makes them laugh. We want the players to experience emotional confusion, with different waves of emotion surging forward at the same time, and they don’t know whether to laugh or be touched as they feel a complex mix of emotions. The dialogue with Shiroko Terror was made with that aim.

—Jokes often have a physical element, like someone’s body suddenly stretching, for example, but what’s impressive about Blue Archive is that it creates jokes with just illustrations of the characters standing or of their faces.

Yang:

What we are mainly using in Blue Archive is a manzai-style comedy based on verbal exchanges. This is largely due to the limitations of the medium and genre. If we were creating manga or anime, we’d probably depict jokes that make amble use of movement.

The reason for choosing a manzai-style was because it was the most suitable solution where we could only use character illustrations and text, but it wasn’t what we sought to do from the start. It is simply the means to an end, not the end itself.

—I think such limitations are exactly what make it a striking form of expression. Take the characters’ facial performances for example. I am especially fond of the facial expression that one of the members of Gehenna’s School Lunch Club, Fuuka, makes when the Gourmet Research Society bothers her.

Yang:

Realistically speaking, it’s a lot of work to change a pose when it comes to illustrations, but changing just a facial expression is relatively low-cost. That’s why we requested that the illustrators create a variety of facial expressions for characters once they were drawn.

It’s interesting that you gave Fuuka as an example. Nuudoru, who was in the illustrator for that one, drew a lot of facial expressions that I hadn’t even requested, saying that I could use them if I liked. And I since actually liked them, I used them.

—There are a vast number of characters in Blue Archive. Even so, there isn’t really one character designated as the joke-teller. Even characters who look like they could fall into that category have both comedic and serious sides. To what extent were you conscious of this multifaceted quality when creating the characters?

Yang:

Of course we were conscious of it. This is also something done well in Gintama. In that manga, all characters have both a comedic side as well as a serious side.

Many staff members are involved in creating the characters, but a premise for that process is that everyone in the game’s world can equally become a comedic character. These characters were born into such a world, so it’s natural for them each to have a comedic element.

In the first place, the characters’ charm comes from their unexpectedness. You could also call it their element of surprise. Even in reality, we are drawn to someone because of the continual curiosity we feel toward them. This human interest results from the slight disconnect with our expectations or predictions. Because the personalities of stereotypical characters are distinct, you can more easily portray them in a way that catches the player off guard. If you use this skillfully, you can create lively characters.

This is what happened with Hanako. When I asked the art director to create her, I asked for the typical clean-cut character, pure and innocent. However, as I was writing the scenario, she became more and more twisted, resulting in the character we have now.

Maybe this is more of me admitting I’m a twisted person rather than me explaining my method…

Saito:

I sense an aspect of idealism within the story and world of Blue Archive. Could there be a deep correlation between this and a world where jokes are possible?

Yang:

There’s probably an aspect of remembering to stay positive in a harsh world, which allows the characters to be humorous. When creating Blue Archive, I didn’t want to conform to the gloomy post-apocalyptic world that was trending at the time, whether that be the visuals or the story.

Gags and jokes have a close relationship with morals. The essence of comedy is purposefully bringing up and playing with taboo topics.

It’s a world where taboos are tolerated, making it an optimistic one to some extent. Not in terms of the story or details, but on a more abstract level.

—Speaking of the jokes in Blue Archive, I think it’s interesting how the jokes were well-received by users and eventually were reproduced as internet memes. For example, the line on the title screen where Swimsuit Hoshino complains, “It’s so hot! I’m not even moving and I’m already sweating!” went viral among the Japanese fandom, resulting in a lot of fan-made music videos.

Yang:

Of course I know about that Swimsuit Hoshino meme. I recognize the importance of feedback when selling a product, so I constantly check on user reactions.

User-made memes are out of our control, but content is emergently interpreted by the receiver. It makes me very happy as a creator.

And especially with Swimsuit Hoshino, I think voice actress Yumiri Hanamori’s great performance is largely to thank. When it comes to recording voices, we do direct from Korea to an extent, but for the most part, Yostar’s Japan studio does the recording for us.

The voice actress gave a wonderful performance that not even we anticipated, then the staff did a professional job with the post-production, and then Japanese users found it entertaining in a favorable way, making it into a meme. You could say it was an accidental phenomenon that resulted from the interaction of multiple actors.

The accumulation of such coincidences is also what makes GaaS games entertaining. Something amusing occurs from something unexpected, and then the fans and creators accept that and develop it together. It’s a lot of pressure for us to communicate with our fans, but it also energizes us at the same time. It’s like jazz improvisation.

The Philosophy Behind Blue Archive

Saito:

Blue Archive skillfully puts the player in the shoes of “Sensei” [the Japanese word for “teacher” and what the player character is called]. How much do you intend for the player to experience this “Sensei” role?

Yang:

We try to not go into too much detail on the personality and characteristics of Sensei. This is to make the player more easily empathize with Sensei. Because of this, the character of Sensei may seem ambiguous at times. However, that’s a good thing because Sensei acts as the user’s avatar.

In my previous work QURARE, numerous difficulties arose from making the player’s–or the protagonist’s–point of view that of the beautiful girl character herself. The protagonist had to appear in every scenario, and this limited our storytelling.

Sensei in Blue Archive is a receptacle for the player’s empathy while also being one step removed from the story, observing the events surrounding each girl. Sensei’s position made such a multi-protagonist story possible.

Saito:

I, too, am charmed by Sensei’s maturity. So much so that I want to be a good teacher myself.

Yang:

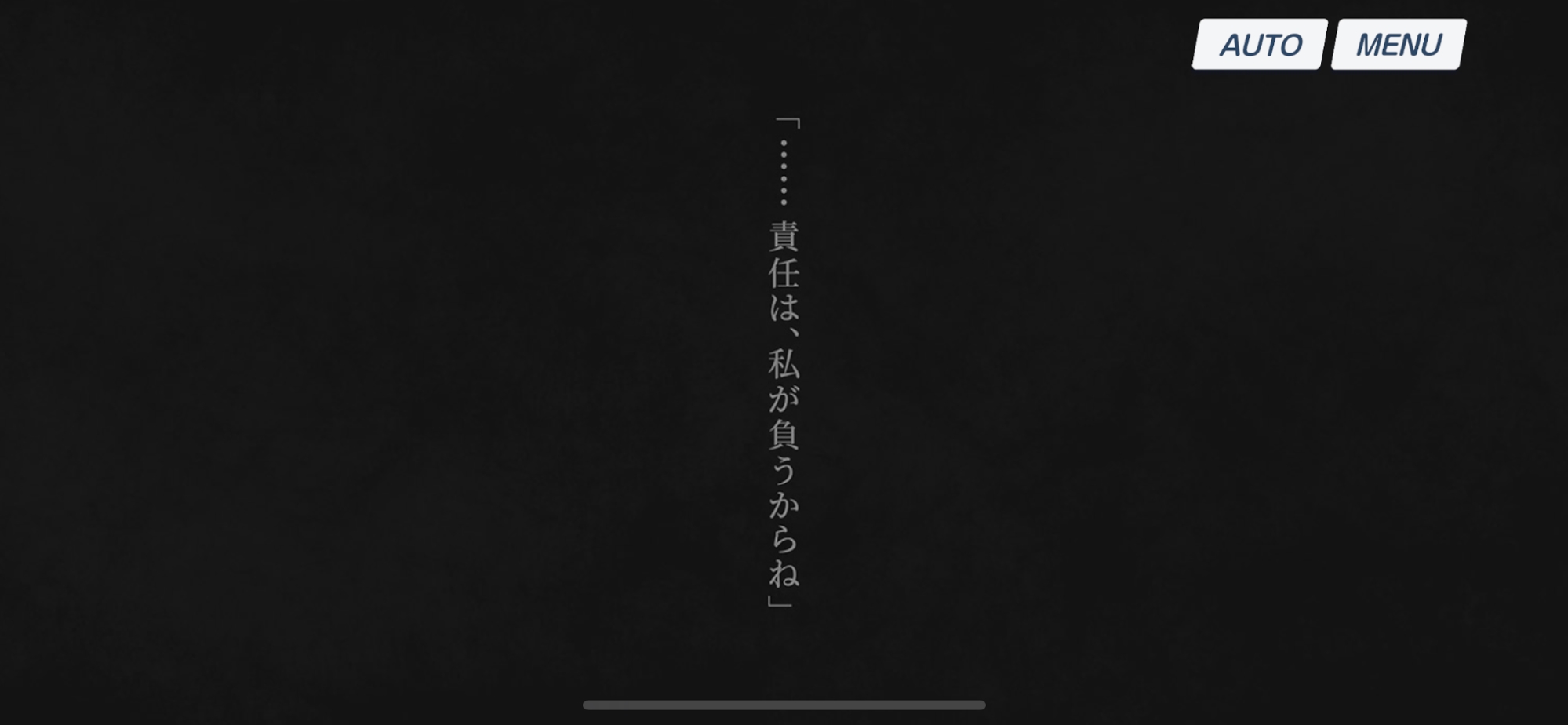

I feel both grateful and responsible to all our players regarding how they perceive the Sensei avatar, and in turn how the story of Blue Archive is interpreted and what sort of influence the work has on them.

I wanted to take my dissatisfaction with this world and ask, “What is it that makes an adult responsible? Are there any adults who will take on responsibility in this world?” However, that’s not my reason for creating Blue Archive. As I said earlier, these questions are simply things that emerge naturally, like fingerprints.

However, I respect you, Saito-san, for your desire to be a better teacher. I hope that you channel that feeling into doing good things when you come back to the real world.

I am human too. I may be an atheist, but somewhere within me I have desires and longings for some sort of mighty existence. But I want Sensei to remain simply themselves.

As Nietzsche said, you cannot feel hope if you do not first find the light within yourself.

—I think what’s great about Blue Archive is that it leaves a strong impression not on players of one single cultural sphere, but on all sorts of players around the world. Why were you able to achieve such universality?

Yang:

Nowadays, a theme pursued around the world may be that of the absence of responsible adults. This may especially resonate among those in East Asian countries, like Japan, China, and Korea, which consume similar otaku culture.

However, we don’t take this universality into consideration at the core of the work.

I fear Blue Archive deviating from entertainment and becoming literature. I’m frightened it will be criticized for acting like part of the arts. I obsessively pursue my goals of maintaining my identity as a company employee and never letting the game stray from being entertainment.

—But don’t the concepts of literature, entertainment, universality, and themes overlap in harmony within otaku culture? Take director Hideaki Anno, whom you’ve openly said you’re a fan of. As you know, his works include glimpses of fatherly absence, a characteristic theme in postwar Japan, and they can be appreciated on a certain literary and artistic level.

However, Evangelion is also a sci-fi anime jam-packed with spectacular giant robots. Entertainment and questioning coexist within Eva as well, though they may differ from Blue Archive in form slightly. Or, in the 90s, when Eva was popular, sharing feelings about fatherly absence was itself a trend in entertainment.

Yang:

I see. Interesting. The topics that you, Jini-san, bring up overlap with themes that I have been exploring deeply for a long time. I would like to take this opportunity to talk about these topics.

I define myself as a foreigner to otaku culture.

Any culture has local characteristics of the country or region where it was born. The same is true of Japanese otaku culture. The theme of children having to overcome and conquer a world created by adults (fathers), seen in the works of directors Yoshiyuki Tomino and Hayao Miyazaki, is, as you say, a theme unique to postwar Japan.

In addition, every work includes the writer’s own humanity. I heard that Miyazaki reflected his father, who worked at a munitions factory, in the father character of Shoichi in his work The Boy and the Heron, and I also heard that Anno’s father had a prosthetic leg, which was reflected in the characters he portrays as broken or lacking in some way.

The theme of absent fathers, born from this cultural and artistic localism, is a common perspective on adults in Japanese otaku culture, a common theme, but it has also resonated with and moved people all over the world, and continues to be supported to this day.

However, when presented like this through Japanese otaku culture, there were both commonalities and differences between the societal issues perceived between Japanese people and myself as a Korean person. When it comes to Hideaki Anno’s works, I first experienced Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water at age 11, and then Evangelion when I was a second-year junior high school student. I was probably just as crazy about these works as any Japanese viewer, but I also enjoyed them through the filter of being Korean on some level. I thought on questions posed to Japanese society from the context of Korean society.

In other words, I was observing Japanese themes from a different angle than Japanese people. That’s the reason why I consider myself–or rather, otakus from Korea, China, and other countries, including myself–to be foreigners to otaku culture. And we create works with our sentiments and discrepancies as foreigners.

Thinking about it, it’s not uncommon for a whole new product to be born when a certain local cultural aspect gains global popularity and is imported into another cultural sphere, where it is reinterpreted from the perspective of the people of that region.

The spaghetti Western is a prime example of this in which Western films were created in Italy after being influenced by American Western films. I think the works we create from being influenced by Japanese manga and anime are probably much like spaghetti Westerns.

—I think the metaphor of spaghetti Westerns is very accurate. The spaghetti Western movement saw Italian directors like Sergio Leone shoot Western films using actors like Clint Eastwood and shook the morals and values that were dominant in America at the time.

In other words, Americans who were the first to create Western films were surprised by the Italians’ perspective. They felt that these were the true Western films. In that regard, I think Blue Archive, which has attracted a lot of Japanese fans, is very much like a spaghetti Western.

However, the creators themselves probably weren’t necessarily conscious of creating an alternative to the American version. They just aimed to create entertaining and interesting films, and it just so happened that they received critical acclaim.

Yang:

The crossing of borders and mixing of cultures should be welcome in otaku culture.

In fact, Japanese otaku culture has a very big impact both consciously and unconsciously here in Korea and in China. When it comes to games, a good example of this is games in which you gather appealing characters and make them battle–the genre called “social network games.”

As works with such ideas are exported and expand globally, games arise from new countries with new perspectives, like Blue Archive, diversifying and adding more meaning to the current state of otaku culture.

When I call myself a foreigner to otaku culture, I don’t mean it in a negative way. I’m a foreigner in that I wish to take part in the large global trend and spread this culture as an outsider to Japan, the former mainstream for otaku culture–as someone outside of the realm where meta acknowledgment is possible.

From this perspective, I wanted to portray Sensei in Blue Archive not with private father-child relationships within a patriarchal system, but as someone with more social responsibility. The structure of an adult protecting a child is different from the relationship between father and child.

And I have one earnest wish: that you will treat the characters as people.

Data is information. Characters are living entities.

Characters are entities projected by humans. Characters are a reflection of ourselves, and we ponder on our own lives through the stories that the characters experience.

For this reason, in Blue Archive we tried to take into account all the virtues and faults that people possess. It may have been a risky choice from a marketing standpoint, but I thought it was a challenge worth giving a try.

I proactively make characters who are easy to hate as villains, like Mika and Saori, and also others like Haruna. Of course, there may be some users who cannot accept these characters.

Nevertheless, however, I hope people will accept this absurd, nonsensical world in which they live as “real.”

Their flaws are what make them human. And because they are human, they possess verisimilitude, making them objects of affection. Sensei both saves and is saved by such characters. Maybe what I wanted to depict was a story in which such joy is shared.

—That human nature of the characters in Blue Archive has undoubtedly led to their popularity among users… By the way, you said “villains, like Mika and Saori, and also others like Haruna,” but wouldn’t Haruna be surprised to hear herself listed? (laughs)

Yang:

Haruna is, in a sense, a villain who shows no remorse. Actually, she probably doesn’t even think of herself as a villain. That is to say, she’s not a villain in a serious sense, but I find myself worrying if there is something wrong with me for thinking that a character like this would really be accepted by users, so in my mind she falls into the same category as Mika and Saori.

Saito:

Let me ask one last question: the title “Blue Archive” contains the word “Blue”, signifying adolescence, with us as Sensei watching over. Why is it that we protect this adolescence? Why must we?

Yang:

I’m already 43-years-old, so I can’t call myself a young person. But I was young once. When thinking back on the old days, I feel that those in the midst of adolescence are not aware of how valuable it is.

And why should we protect adolescence? I don’t give a reason or justification for that question to users. Or rather, I don’t have a justification.

That’s up to the user. The user themselves must protect because they believe protection is necessary.

If the user judges it to be unnecessary…Well, that would be a failure of the game’s design.

Saito:

With those words at heart, we too will have the courage to continue to protect adolescence.

–Thank you very much for today. Lastly, we’d like to ask you to give a message to our readers.

Yang:

I’ve spoken a lot on the topic of Blue Archive, but Blue Archive is ultimately content that belongs to the company, and I’m simply an employee belonging to that company. Blue Archive is the result of a labor contract between me and the company. This mundane truth is also a source of my motivation.

I am not Blue Archive. I create it with a team. Blue Archive is the result of a variety of people painstakingly creating something together. There is myself, of course, but there is also Executive PD YongHa Kim, game director JongGyu Lim, art director In Kim, project director ByungLim Park, everyone on the scenario writer team, all the composers, all the artists… The list of names goes on and on. So many people have supported us both from within our company and from outside it to make Blue Archive exist in the world.

And to all the players, I am grateful for your love for Blue Archive. And at the same time, I’m cautious so that I won’t take your kindness for granted and become lazy.

As someone who creates stories, I wish to continually pursue storytelling, never growing complacent with my current success. I want to keep working hard without losing my sense of self.

Lastly, I would like to finish with a proverb from Buddha and my motto:

“All wordly things will perish. Be diligent and do not be lazy.” (Nirvana Sutra)

Once he got going, Yang spoke eloquently without so much as a pause, quoting from his vast knowledge on topics ranging from manga to philosophy. We were overwhelmed by his intellectual, passionate speech, but we also sensed his deep love for his work and his gratitude toward his fellow staff members.

Yang humbly refers to himself as only a company employee, yet Blue Archive undoubtedly would not have achieved such a high degree of perfection without his intelligence and enthusiasm.

Will his wish for users to accept the characters as living entities get across? Perhaps to those who have played Blue Archive, they don’t even need to be asked.

From a literary scholar to a game developer, from a 2000s otaku to a creator in the TikTok era, from a foreigner to otaku culture who loves Japanese anime and light novels to the mastermind behind the Korean game equivalent of the spaghetti Western–Yang crosses all sorts of boundaries, connecting cultures.

And Blue Archive, too, has gained the clarity to go beyond countries and time periods with a commanding view of the world.

What tales will be spun next? We’ll be keeping our eyes on Yang.

Lastly, we would like to take this opportunity to thank the head of Vittgen Inc., SangHyun Bae, for his assistance with the interview setting, and rondo who interpreted.

Indie Intelligence Network plans to continue publishing long interview articles.