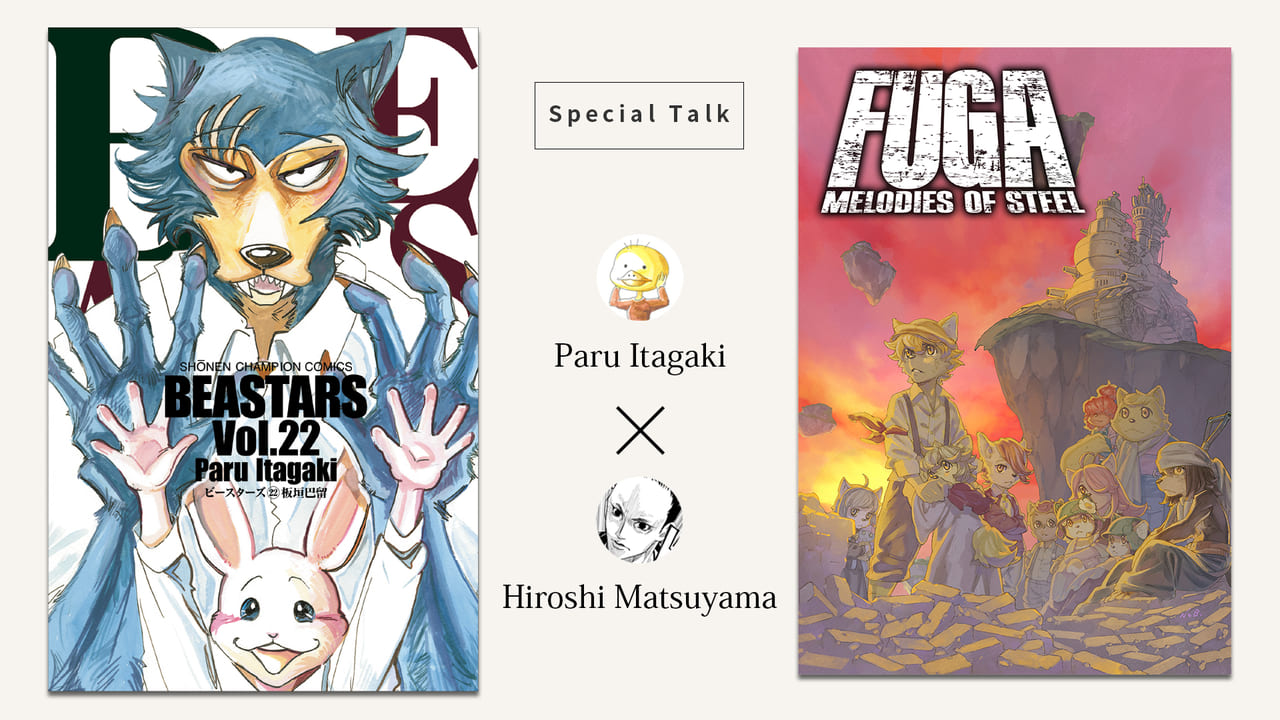

Fuga: Melodies of Steel, an emotionally compelling RPG featuring 12 children thrust into the midst of war, was released on July 29th, 2021. It’s the newest installment in the Little Tail Bronx series, a series known by fans for depicting a world inhabited by Caninu (dog people) and Felineko (cat people).

For CyberConnect2 (also known as CC2), the company behind Fuga, the series is extremely essential as it’s set in the same world as their previous titles, Tail Concerto and Solatorobo: Red the Hunter. This is also evident in the fact that Fuga: Melodies of Steel is CC2’s first self-published game title. (To read more about CC2’s dedication to Little Tail Bronx, the kemono genre, and more, go to this article (in Japanese language only).

Speaking of the kemono genre, a groundbreaking manga that burst onto the scene in the late 2010s might come to mind for a lot of people. Of course, we’re talking about Paru Itagaki’s BEASTARS, serialized in the manga magazine Weekly Shonen Champion from 2016 to 2020, and recipient of numerous awards including the 2018 Japan Cartoon Grand Prize. Its anime version aired on TV in 2019 and 2021, and new episodes will be available on Netflix in the future.

At the beginning of BEASTAR’s story, the curtains rise to reveal that an alpaca named Tem has been senselessly killed and devoured within the walls of the boarding school, Cherryton Academy. Such an act is extremely taboo in a world where herbivores and carnivores peacefully coexist.

The world in Paru Itagaki’s BEASTARS appears to be a paradise where adorable animals live in harmony at first glance. However, looks can be deceiving; beneath the cuteness lies a sense of distortedness and anguish unique to this kemono world. The technique BEASTARS uses in depicting the essence of humanity through the world of animals shares resounding similarities with the technique used in Fuga: Melodies of Steel; animal children ride aboard a giant tank and come face to face with the realities of war.

With this in mind, Denfaminicogamer organized a discussion between BEASTARS creator Paru Itagaki, and CyberConnect2 CEO and Fuga executive producer Hiroshi Matsuyama. Held remotely via online conference call, they were also joined by the editor-in-chief of Weekly Shonen Champion.

- Paru Itagaki

- Hiroshi Matsuyama

The talk was set up based on their similarities with the depiction of human society through the world of animals, but as Matsuyama is a self-proclaimed “number one manga lover in the gaming industry,” the topics which came up varied widely, from BEASTARS and the kemono world, to Paru Itagaki’s latest work SANDA and the production process itself. A must-read not only for gaming fans but manga fans as well!

Interview by/TAITAI & Kodai Kurimoto

Text by/Seinosuke Ito

Edited by/ Kodai Kurimoto

English translation by/ Travis Proo & Irene Ladignon

English editing by/ Liam Holton

日本語版はこちら:『BEASTARS』板垣巴留×『戦場のフーガ』松山洋 ケモノ対談 ――「理性」と「野生」のせめぎ合いから生まれる創作の極意(2021年10月6日公開)

In the first chapter of BEASTARS I saw the word “shokusatsu” and I felt like I’d been struck by lightning.

*shokusatsu (食殺)

Cannibalism in the world of BEASTARS. The term “devour” and its derivatives will be used as a replacement.

Matsuyama:

Can I just say this first? Usually when you do interviews, Paru-sensei, you’re often seen wearing a mask and concealing your face, so I never knew what you looked like. You’re so young!

|

Itagaki:

I’ll be 28 this year.

Matsuyama:

What!? [You look so young that] I thought you were a college student! What age were you when you began the serialization for BEASTARS?

Itagaki:

Immediately after graduating from college, I’d say.

Matsuyama:

Sorry for being this shocked old guy all of a sudden (laughs). You’re just a far cry from the image I had conjured up of you in my head, so I’m just stunned.

Itagaki:

No, it’s fine.

Matsuyama:

So, we actually put together a “kemono” themed game called Fuga: Melodies of Steel, and when we were thinking of a plan on how to hype up our game, Den-fami approached us. They said that we should try getting in touch with you, since our game and BEASTARS are both connected in that they both feature “kemono.” I honestly thought to myself, “We are not worthy!” (laughs) So, apologies if I’m acting all strange.

I was a bit late in telling you this, but I adore BEASTARS, and I think the latest chapter of your new serialized title, SANDA, is really great as well!

Itagaki:

Why, thank you.

Matsuyama:

BEASTARS certainly was a shocker though. It’s not that there weren’t any kemono-type manga out there, but the day that serialization began for BEASTARS I knew this story would be a whole new approach [for the genre]. I mean, the term and concept of “devouring” basically tells the whole story right there, doesn’t it?

――The impact of the term “devour” is really something else.

Matsuyama:

In the world of “kemono” that’s definitely something you shouldn’t be doing in your products, right? These herbivores and carnivores are going to school together, and the moment you instill that world view that you could be eaten by the guy right next to you, you have this totally insane product on your hands! (laughs) I actually talked about this and about Weekly Shonen Champion having other “quirks” like it with some other manga enthusiasts.

Itagaki:

(Laughs)

Matsuyama:

Our new title, Fuga: Melodies of Steel, actually started 25 years prior with the creation of another title of ours, Tail Concerto. These two, plus our other game, Solatorobo: Red the Hunter, are all a part of the same kemono world.

When we sat down to make this animal-based world, the first thing we decided on was to limit its inhabitants mainly to 2 different types of people: the Caninu and the Felineko. If we hadn’t had narrowed the races down like we did, we’d have run into the inevitable question of “What type of child would be born from a love pairing between this and that kemono race?”

Just like with humans not knowing if their child will be born a girl or a boy, we run into a similar situation where we don’t know what the child of a Caninu and Felineko pairing would be.

――And what do they even eat?

Matsuyama:

Do we have Caninu and Felineko eat beef, or do we have them only eat vegetables and nuts? The latter isn’t true [in reality], and with that in mind we created the in-game livestock called “giu,” that they use for food. Not only that, but we have also introduced some distortedness to the world setting as well. The majority of the populace is made up of Caninu, and with that and their differing origins from the much smaller Felineko population, there exists some mild prejudice towards the Felineko.

|

In other words, these are things that occur in the real, human world as well, wouldn’t you say? We have schematized these concepts with these animal characters, making it easier for both children and adults to enter into this world. People think, “They’re only animals, so why do I empathize with them?” Our strategy was to design the world in a way that would best convey that concept.

I rambled on a bit too much about our games’ setting, but simply put, a kemono world has quite a few delicate areas, doesn’t it? We had to consider a lot when making our world, but for us, the big “DO NOT TOUCH” area that I had mentioned was precisely what BEASTARS included with the concept of “devouring.” The word itself is phenomenal, I thought.

Itagaki:

Yes, I suppose it is (laughs).

Matsuyama:

The second I saw that word, I felt like I was struck by lightning or something (laughs). When BEASTARS emerged, I thought, “Something major just hit the scene.” I mean, you depict both carnivores and herbivores, as well as life and death in your kemono setting, and you draw it in such a miraculous way that hides it. This is probably the most indecent way you could have done it in, too! (laughs) The word “murder” sounds good and all, but these people are eating each other!

And so, I want to ask you: Were you the one who said to include “devouring” at the center of this world’s mysteries and incidents, Paru-sensei? Or did your editors tell you to dive in a little deeper here? Could you tell us want went on there?

Itagaki:

Who was it, now…? Anyway, by making the one thing that should never happen occur right in the very first chapter, I thought it would be good for describing the world setting.

And for me, I never really thought much about trying to make the “devouring incident” itself the focal point of the story. But later on, our lead staff asked me who the culprit was and I realized, “Oh, I need to decide on that.”

Matsuyama:

Yes, you do (laughs).

Itagaki:

Personally, I began without really comprehending how to write a manga, and so conversely that ended up feeling more natural, I think.

Matsuyama:

THAT’S how it all came about!?

Itagaki:

Yes, that’s how it went.

――I think that behind this unique perspective that BEASTARS has, that there must have been something that you yourself felt was off in day-to-day life.

Itagaki:

Originally the world of BEASTARS was something that I had stewing in my mind throughout my junior high school and high school years.

When I was a child, my friends would look at pictures and anime featuring animal worlds and would say things like, “It’s funny because the dog character is walking a dog,” and the like. I mean, I know kids would say things like that to look and sound smart. But for me I would think to myself, “Keep your lame feedback to yourself!” From that, I thought up the world of BEASTARS, which I wanted to be “a story that no child would make such lame comments about.”

An important theme for me was to have some sense of satisfaction, and that’s the feeling I had while working on this.

――I’m just curious, but did you happen to see the Disney film, Zootopia [*], Paru-sensei?

A CG animated production, created by Walt Disney Animation Studios and released in 2016. Centered around the titular paradise where animals live as if they were humans, a rookie rabbit cop and a swindling fox team up to unravel the secrets of their paradise. While having animals as their motif, there are depictions of real-life social issues such as racial discrimination.

(Image from Disney’s Japanese Official Website – Zootopia)

Itagaki:

I did. It released just around the time when BEASTARS began its serialization, and so I watched the film with a certain “alertness” about me (laughs). The film had so many people working on it, and it was so well made. But I did think its ending wrapped up just like any Disney movie would. Things happened not so much because they were animals, but because they were more human-like.

――Based on what you’re saying, your sense of satisfaction with BEASTARS rings incredibly true, doesn’t it?

Itagaki:

But, the fact rests that it’s because of Zootopia that we have a large number of people who watched [BEASTARS]. That in and of itself makes it a wonderful piece, I think.

Our main goal is to “get people to enjoy reading our manga week in and week out.”

Matsuyama:

Shonen manga usually have some goal like “I want to meet my dad,” or “I want to be the pirate king,” right? And most stories are written to show the protagonist growing in order to achieve those goals. However, Weekly Shonen Champion has a surprising number of stories that don’t present such goals in them.

Itagaki:

Yes, that’s true.

Matsuyama:

Take Legoshi, the protagonist of BEASTARS. He doesn’t have any clear goals or dreams that’s established in the beginning, does he?

Itagaki:

No, he doesn’t.

Matsuyama:

But in the end, looking back on it all, it’s definitely a shonen-type manga.

――Is there some reason behind not presenting a goal?

Itagaki:

I wonder…

Matsuyama:

I think both methods exist. The need to declare one’s goals in a shonen-type manga is probably the thought process behind Shonen Jump.

Because with Jump, if you don’t capture attention and popularity with the first chapter [of a story], then there’s no way that story can continue. So, establishing what the protagonist wants and why they want it from the beginning has mostly become the template for Jump, I think.

On the other hand though, there are also exciting story beats where the protagonist gets embroiled in some incident and you as a reader want to know what happens. I think the latter example is more of what Paru-sensei was going with.

Itagaki:

Yes, it is. In my case, the goal is for readers to continue to enjoy reading week in and week out. If we were to go with too long-term of a goal, then I think we would only be hedging ourselves in, so to speak. The moment the protagonist finds their goal, they would joyously announce it to everyone, yes, but until then our method is to just go week by week.

Matsuyama:

Just out of curiosity, do you keep track of where to cut off for each individual volume?

Itagaki:

We did for volume 1, but not for volume 2 and beyond.

Matsuyama:

Oh, really? I re-read the story through each volume, and I seriously thought your cut-off points were stellar!

Itagaki:

We’ve made a habit of creating some sort of pull each week, and so that cut-off point would be fine no matter where you chose to put it.

Matsuyama:

What does the editing team think?

|

Editor:

We do convey things. Generally, our volumes extend to roughly nine chapters, so when we’re around three chapters away from that point we inform [our writers] that we’d like to “wrap this volume up at XX amount of chapters.” However, that’s all we tell them really.

Itagaki:

If I were to write thinking, “This is where the volume cut off will be,” then it might make me feel like the previous chapter will need to be made to supplement it. That’s the one thing that I want to avoid. I want to give each chapter my all.

Matsuyama:

In preparation for this meeting, I actually re-read through every volume of BEASTARS, and I felt like it was well thought out and calculated. Of course, there were parts where it felt like maybe you were hitting the ground running, but some parts really made me think, “Just how far ahead have they calculated!?”

Take for instance the developments later on. Particularly in the beginning of the story, I was reading and kept telling myself “no way,” but even then, the thought of “maybe the culprit for this ‘devouring’ is the protagonist Legoshi himself!” stuck around. This is because Legoshi tended to get a bit woozy at the scent of blood, and it’s not something that a protagonist should be revealing! That sort of insecurity lasted for so long! I got hooked and wanted to read it every week.

Itagaki:

Thank you.

Matsuyama:

For the editing team at Weekly Shonen Champion, how much did you consult regarding big changes and the like?

Editor:

I was in charge of volume 12 of BEASTARS, and I would from time to time speak with Paru-sensei about things to the degree of “I would like to see more of this.” It was similar to when the original lead would ask who the culprit was, in that I would read the story, find something I would be curious or concerned about, and then speak with her about them directly. She would then work to deliver on those things, and that was basically it, I think. I didn’t really speak with her on things to come in the future.

Itagaki:

That’s true. We never talked about that sort of stuff (laughs).

Editor:

Our meetings were less about structuring and were more along the lines of, “We’d like to see more of this,” or, “wouldn’t it be better to go in that direction?”

Matsuyama:

So, it was an ideal setup of sorts, then? Placing the focus on the writer and keeping involvement to an appropriate level.

|

Itagaki:

True. They really let me draw what I preferred but were there to offer advice when my depictions weren’t doing so well, so I think it was an ideal setup.

Editor:

The only request I ever made of Paru-sensei was, when she reported in that the serialization was almost over, to try and extend it for just a bit longer, since we had the anime, too. As a result, we managed to get about one or two more volumes than she had originally anticipated.

Matsuyama:

You just went full businessman on me there (laughs). But that climax never made me feel like there weren’t any wasted components—almost like you had anticipated this from the start.

Itagaki:

Thank you very much.

Everything is connected without any contradicting points, and it’s all because it was created with the mind of one person.

――When something is made by a team or organization, the group needs to consult with one another, no? To have something that everyone is satisfied with, you’ll have to make compromises somewhere no matter what. If someone were to solo something they could probably work 100% towards what they want, but a team has the task or issue of bringing everything together, resulting in only about 80% of everyone’s potential [being brought out].

Whether it’s an anime, film, or game, pushing out a large amount of creativity when producing something as a team is a major task. Of course, there are rare individuals like Hayao Miyazaki who could push through all on his own with his incredibly unique style.

On that note, while manga may have meetings that might occur with the editors, they are generally created by individuals, and I have a feeling that the high level of purity there exists because they are working alone. In your case, Paru-sensei, where do you find enjoyment in drawing manga?

Itagaki:

Whenever I watch an overseas drama, I see these well-devised stories and their ability to foreshadow and end without any inconsistencies. There is that side that I like and enjoy, but I think that on the other hand there’s a certain distinct stimulation that you can get from something created by one person.

In my case with BEASTARS, the idea of “one of the club members losing an arm and that incident letting you figure out who the culprit is” is something that I feel could only be conceived by one single creator. It might be a lot of work, but I think there’s a lot of value behind relying on that sole mind to come up with these ideas.

――Conversely, is there anything that you personally admire regarding creation on the team level?

Itagaki:

Sometimes when I’m exhausted, I just wish that I could brainstorm with a large group! (laughs). However, there is this harsh reality where it’s far more interesting to have a single writer come up with ideas on their own instead of stewing up ideas all night with their editor. For that, I just cannot ask them for help.

――As the CEO of a game development firm, what do you think about this, Matsuyama-san?

Matsuyama:

I think that in the end it’s the same for us, too. For games and films we have directors in place, and those directors are considered to be “kings” who decide on everything.

|

However, games have so many elements to them that it’s just not possible for the director to be involved with them all, and so we need to rely on lead staff to decide on each individual part of the game. When you look at each part piece by piece, you might give them maybe a 60 or 80 [on a scale of 1~100]. But, when you look at a game or film in its entirety, it’s all a matter of whether or not the director will say “this is a 100 for me.”

I think the area where you see the smallest number of people working is probably in manga production, I’d say.

Itagaki:

That’s true.

――In that sense, I think that while the Fuga: Melodies of Steel project certainly was a team production, size wise it would seem easier to become displeased about aspects of it [as a leader].

Matsuyama:

When creating a character-driven game from a borrowed IP it’s a given, but you have to take into account the concerns and conveniences of manufacturers, the original creators, and the publishers, and you have to find optimal solutions to appease them all. In our case with Fuga, we got to decide everything from the ground up, and while there was a sense of joy and freedom from that, we now have to answer the question, “Well, what do we go off of to make this decision or that choice?” The possibilities are endless, making us just “settle,” but then we all worry about if we made the right choice or not.

In the end though, it’s the director that overlooks everything, and they have to make justifiable decisions on what they want others to do. In a sense, you could call that the preferences of that particular individual, but that was the only way we could decide on things. The sense of speed here was far different from when working with partner companies.

|

For me, the scale of something like Fuga: Melodies of Steel was somewhat the same feeling as when creating a manga by yourself, like with coming up with those moment-to-moment ideas. We had a limited amount of personnel and time, and almost none of that time could be given to worrying.

――Paru-sensei, earlier you mentioned trying to have readers enjoy your manga from week to week. I think that’s the weekly, serialized manga format, but with the culture of extending the length of a picture story, I feel that this culture places a heavy emphasis on that sense of being “live,” or in real time. This is a bit of a naïve question, but what do you think this “feeling of having live, weekly serialization” might be?

Itagaki:

You’re right, I do think that weekly serialization is quite special. Each week has a deadline that’s approaching.

There are a lot of necessary elements in a story, such as properly connecting chapters, foreshadowing, and avoiding plot holes or inconsistencies. However, I think there are also many stories that were too fixated on such elements and ended up becoming stale because of it. The first editor I worked with basically told me to “keep it interesting.” (laughs)

Matsuyama:

That’s pretty encouraging! (laughs)

Itagaki:

They said, “Just keep it interesting each week and it’ll be fine.” That’s all weekly serialization is, really.

――But like Matsuyama-san pointed out, BEASTARS does have good cut offs, and after reading through its entirety it does feel properly constructed. Why do you think that is?

Itagaki:

While I was working hard, creating interesting stories from week to week, in the end I was still thinking up everything on my own, and it somehow mysteriously connected well without any inconsistencies (laughs). I would think, “I can do this pretty well!”

Working carelessly could result in some plot points not connecting properly, but if you are true to your work, then I think you can manage.

――You say “make it interesting each week,” but do you ever feel like you’re always thinking about areas that make you think, “Wow, this is pretty strange”?

Itagaki:

Yes, I think so, to a certain extent. Both my sense of reason and my wild side clash then! (laughs)

――For entertainment and other things born from creativity, if you are able to explain it, then it’s essentially already done and over, I think, whereas something that is new and cutting-edge that no one’s ever seen before can’t be explained, [and therefore won’t end].

Itagaki:

You’re right.

――And I think that “wild-like” disposition that you mentioned, Paru-sensei, is what usually breeds creative, cutting-edge things.

Itagaki:

I completely get what you’re saying. I think it was my first editor that told me this, but they said, “there’s more appeal to an interesting product that people can’t grasp than an interesting product that they already know.” That statement really left an impression on me. There’s a certain kind of preciousness found in being brave.

――Did you learn or talk about what’s important for manga with your first editor?

Itagaki:

I did. I started off not knowing what I was doing at all, and it was best for me to not take written notes, because what stuck with me to this day were those words of advice.

I’ll always remember the impact of those pieces of advice I was given, like, “Write each piece as if it will be the final one,” or the previous comment about an interesting product that people can’t grasp.

Matsuyama:

Those are such impactful statements! (laughs)

――Are these things that you can’t learn from other manga artists, but rather from your editor?

Itagaki:

For me, my first editor was a major veteran [*] in the industry, and so it felt like I was getting advice from a father figure. He was my Obi-Wan Kenobi.

*Paru Itagaki’s first editor

Takafumi Sawa, editor-in-chief of Weekly Shonen Champion from 2005 to 2017. He also served as the very first editor for BEASTARS.