The more of a veteran manga artist you become, the better you get at being able to pick up ideas from idle chatting.

――I’d like to ask the editor this question, but what type of manga artist do you fashion Paru Itagaki-sensei to be?

Editor:

I originally began my editing career with Young Magazine, working with a number of veteran artists, but Paru-sensei has this veteran air about her, too. (laughs)

It might be a strange way to put it, but I feel this strong drive from her like, “Interesting or not, it’s all on me.” She’s a genius without question—Paru-sensei, stop grinning! (laughs)

Itagaki:

You caught me grinning. (laughs)

Editor:

I’ve worked with a good number of artists, and she’s definitely the genius type. Her naming work was fast, as was her drafting.

What surprised me though was that, even if she gets the OK for her naming and her manuscript would be done, she wouldn’t be satisfied, saying, “I’m not handing this over.” Then, for the next week she would be drawing up to 40 or so pages—roughly double the usual amount—so that we wouldn’t experience any delays.

Matsuyama:

Whaaat!?

Editor:

In that sense, for better or for worse she didn’t rely on us editors there. So, when we did sit down to meet it would be not so much about the work itself, but more so about the latest news, what we thought, and so forth.

Itagaki:

We chit-chatted a lot (laughs).

Editor:

The more of a veteran manga artist you become, the better you get at being able to pick up ideas from idle chatting. One of my predecessors once told me that, “nothing interesting can be born from just looking at a name. Artists don’t think like we do. What’s important is if they are able to take and expand upon the commonplace chatter that you’re doing. So make sure you learn how to chit-chat.” This was the first thing that I was taught.

“Learn how to properly talk with other people, first.” This was how I was trained, and so it was easy to be Paru-sensei’s editor—even fun, I thought. So, in that way she was definitely the “do-it-yourself” type of artist. A lot of veteran artists are like that.

Itagaki:

(laughs)

――From your perspective, Paru-sensei, is there anything that you expect in your editors?

Itagaki:

It’s very true. My editor will not stop talking if you don’t say anything to them. (laughs)

Matsuyama:

Doing what you were taught, I see (laughs).

Itagaki:

It’s fun for one, and for my work in particular, I almost need to communicate and be involved with others, so it’s been really helpful in that regard. But the thing that I require the most from my editors is the ability to honestly tell me if what I’ve made is interesting or not.

――The editor is obviously the first actual reader of the content, but on the other hand, that single reader is just 1 out of an infinite number of other readers, right? So, when that one person says your work is “interesting,” how seriously should you take them? I’m curious about how artists and writers interpret the comments from their editors.

Itagaki:

At our meetings I will say something like, “I want to make the story like this.” Then, I will gauge their reactions, which for the most part will sum up what the reaction of the average reader will be, I think. I’ll listen to the editor’s tone in their voice and look for that “twinkle” in their eyes and just know, “I nailed it here,” or, “Maybe I should mess with that a little more.” It’s kind of become something akin to a barometer for me.

――So your powers of observation are just on another level then.

Itagaki:

Sometimes I feel I have too much of it, and it can be rough, then. It’s almost like I’m hypersensitive.

Matsuyama:

For both our manga and games and their design, setting, scenario and so forth, we have what we call “script debugging,” which is where we bring in people not affiliated with manga production, for example, to look at the naming and whatnot and give their own opinions on them. Those opinions are usually 1 of 2 types, being based on either a “gut feeling” or on what seems “natural” to them or not.

|

Even then, there’s a part of us that aims to get those opinions, so when we do it’s more of a confidence booster for us, like, “OK, we got it!”

Itagaki:

I know what you mean.

Matsuyama:

From there, whenever we would get a comment about something being “strange” in some area that we were anticipating, then we would 100% go in to fix it, mostly because it would be an area that we weren’t too particular about, meaning a fix would totally be fine there. However, if that comment were to be about something we were particular about holding onto, then yeah, we might discuss it, but in the end we would most likely turn that idea down (laughs).

――How do you handle informational input, Paru-sensei? Do you have fairly large discussions with your editors about it?

Itagaki:

While I’m working, I always have our local radio station TBS playing while I chat with other staff, and those conversations can be quite long. We have a few chatterboxes assembled here (laughs). They are all capable people of course, but since everyone can be quite skilled, it’s more about values and how much you are able to speak that’s important for the staff.

――When you say “being able to speak,” what things do they even talk about?

Itagaki:

It’s fine if we have someone opinionated or biased, but we mainly have people who can look at something and provide their personal opinion on what they’re seeing. It’s not about a personality being good or bad, but that trait is important for them to have. In fact, it might even be better if someone were to have more biased opinions, maybe (laughs).

――So someone who has differing values from you, then?

Itagaki:

Yes.

――Paru-sensei, do you have any real-world people in your life who serve as motifs for the characters in your story?

Itagaki:

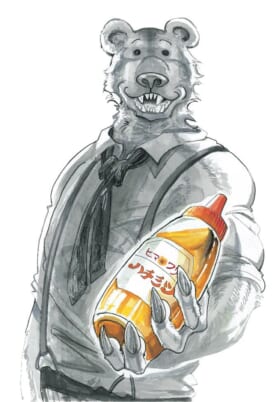

I do and I don’t, but I think it’s important to recognize that there are certain “archetypes” of people in the world. Because my characters are animals, they almost need an excessive amount of realism to them, and so instead of fixating on one type of person, it’s more like “this one is abnormally kind,” or “that one is too soft towards themselves.” With sides like those included, it’s almost guaranteed to make something interesting. Even I serve as the motif at times.

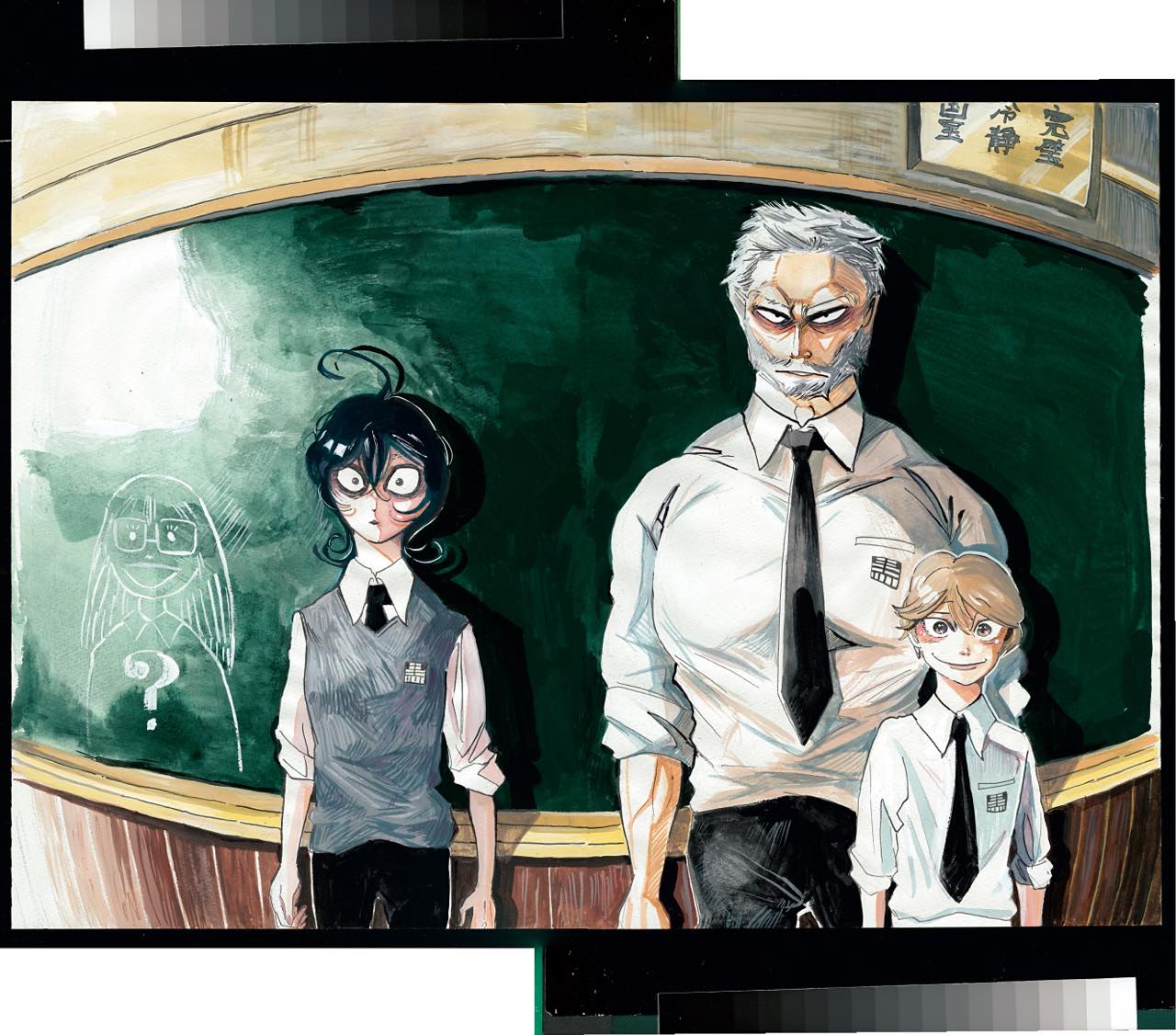

Legoshi’s friend Jack, for example, is a safe zone for him, and is modeled after my own mother. It’s quite common for a lot of the more distinct models to be family members. Gosha is based off of my grandfather. Characters that you have an emotional attachment to are often like that.

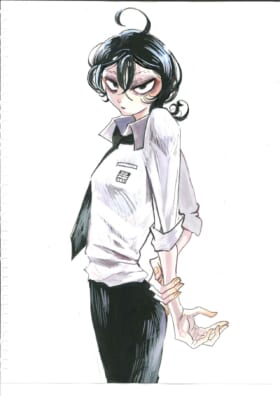

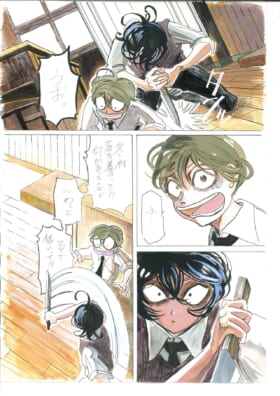

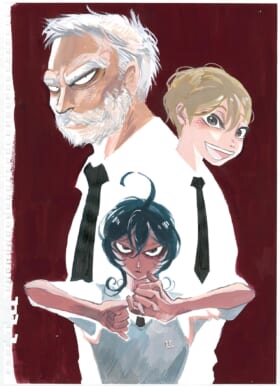

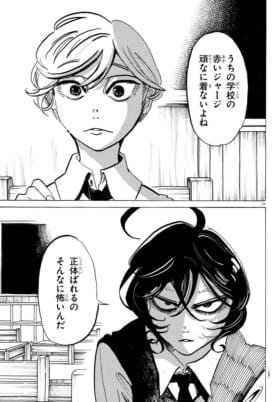

- From the left side, Jack, Legoshi, and Gosha.

The Black Market area was modeled after the Kabukicho district, which I first saw when I was a child. It was a very different place at that time, where you would just see signs with completely naked people on them (laughs). I had to pass through that area to get to the movie theater and my mom would always tell me, “Look down!” while we were walking through.

|

――You were able to make use of those eye-opening things and put them into your work.

Itagaki:

Yes, I was. In the end I think that’s what’s important.

I felt this cool, superhero vibe from Santa Claus, and I fell in love.

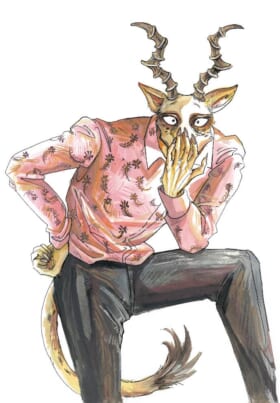

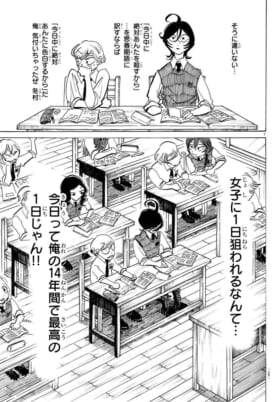

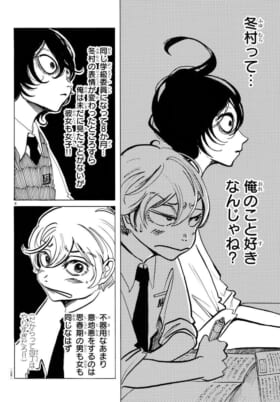

――Your other serialized manga, SANDA, is also really interesting, Paru-sensei.

|

Matsuyama:

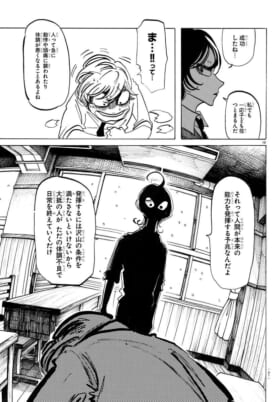

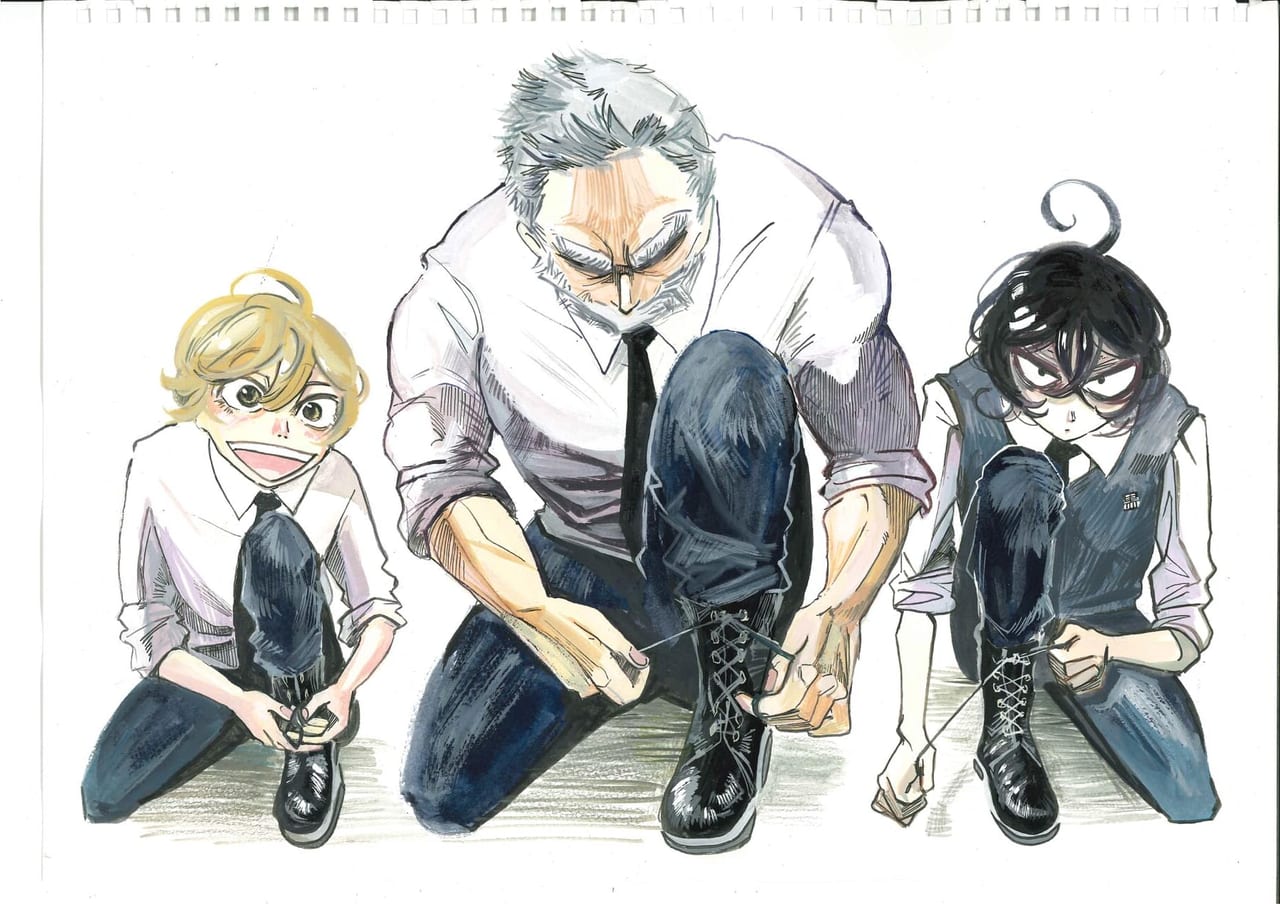

If I were to say you “did it again,” you might get mad at me, but Sanda, the protagonist in this story, doesn’t declare any main goal either. The protagonist gets completely caught up in what’s going on, and so you have no idea where the story is heading.

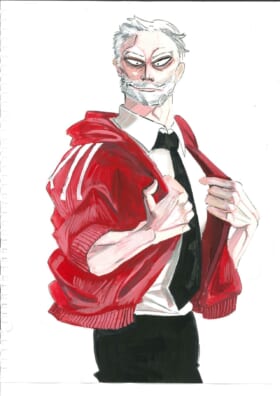

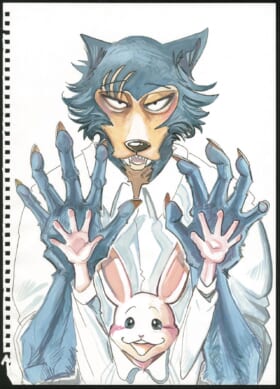

- The left character is “Sanda,” the protagonist of SANDA.

Itagaki:

That’s right.

Matsuyama:

I’m pretty sure that SANDA is your first time creating a non-animal, human-based world, but what’s the story behind you deciding to create SANDA, Paru-sensei?

Itagaki:

Some time ago I had the opportunity to write a standalone story about Santa Claus and a girl from the red-light district for Weekly Manga Goraku. That really left an impression on me, and I thought, “You know, this might be a good theme for a shonen manga.” But, instead of writing it for Weekly Shonen I made a secret deal to release a separate volume for Weekly Manga Goraku. (laughs)

I originally liked wolves, hence my creation of Legoshi, and just like with that, I was fascinated with Santa Claus, too. In the end, I just want to draw things that are connected with my roots or that I’m emotionally invested in.

――What attracted you to Santa Claus?

Itagaki:

No one has ever seen the real person, but kids tell these believable-sounding tales of him, and he’s this amazing man who does a ton of work all in one night. He’s kind of like this chivalrous spirit or some spy from the movies (laughs). He felt like some sort of hero, and that’s why I liked him so much.

|

Matsuyama:

I see, so you extracted that from him, then.

Itagaki:

Right. I see him as this cool, heroic person.

Also, having reached the latter half of my twenties, I often find myself wondering what “growing up” even means. If I made Santa Claus into my motif for me coming into adulthood, then I thought it might be easier for me to write. It was a heavy time for me.

――Earlier you touched on your “feeling satisfied” with regards to your work, but what are you aiming for concerning SANDA?

Itagaki:

Everyone eventually stops believing in the existence of Santa Claus, right? But for me, I always offered myself some internal gratification through my junior high years by telling myself, “Santa might not come on Christmas, but he is giving my presents to my parents, so he must be real.”

So, I’ve currently been searching for a way to make my point, and instead of shocking kids by telling them to believe in Santa, I’m showing them, “Hey, if you look at it this way, then he truly must exist.” That’s the way in which I’m drawing this.

――It’s amazing how all of your responses exceed each of our imaginations (laughs). For the editing team, what did you think after hearing what she wanted to do for the next serialized story following BEASTARS?

Editor:

We heard about it from Paru-sensei right before the time that BEASTARS ended. We knew that she was getting a lot of offers to create a series for other publications, and so having her write for us again was the number one thing for us. We were very happy. Then, when we heard a summary of the story, we thought it sounded interesting, and so we just had her run with it.

――Is there anything specific that’s easy to draw when it comes to animal characters? How about when drawing human characters?

Itagaki:

Hmm…I like that humans can serve as a motif for when I draw animal characters. In a number of children’s stories, most of the characters are in fact animals. And so I think that for a lot of people, the character of Legoshi was a love-at-first-sight type of character right from the start.

However, for human characters, they share the same world as us, and so you really have to consider designs that everyone will love. I’ve had to learn that deeper side of drawing recently.

Matsuyama:

BEASTARS had the peculiarity of being a kemono-type story, and so you would remember certain characters, like “that spotted seal character acted like this” and so forth. They’re ingrained [in your mind], so to speak. And so I was excited to see what kind of human characters you would make, Paru-sensei. Let me just say that SANDA is a unique, one-of-a-kind existence.

|

Take the school headmaster that just made an appearance. Sure, he may have undergone way too much plastic surgery, but to actually show his emotions by using a cane to move his face around? An ordinary person wouldn’t think of that! With just that, I don’t think I’ll ever forget that character. Your ability to have this distorted setting and these brand-new characters is as stupendous as always. I look forward to reading this every week.

Itagaki:

Thank you.

It’s fun working to find a balance that readers can be satisfied with when putting together a world and its setting.

――For CyberConnect2, do you find anything different between when you create kemono games versus when you make non-kemono ones?

Matsuyama:

I do think they’re different, yes. Making a world and its setting is fun! You can’t express absolutely everything in a game, but we do create [as much as we can for] the setting, because if you have that foundation there, then you will have something immersive that allows you to really feel the worldview.

One anime that I have my staff use as a sample and standard is Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise [*], created by Hideaki Anno. In this story, there’s a planet where a group involved in space development launches a rocket. They don’t explain what’s going on with that world’s culture, religion, transportation, or politics, but it’s all been thought up. The entire worldview, or planet in this case, was put together, and when I saw this film—in my teen years, I think it was—it was really impactful.

A 1987 anime film directed by Hiroyuki Yamaga, Royal Space Force depicts the fictional land of Honnêamise, where protagonist Shirotsugh and his companions work together to launch a rocket into space. Hideaki Anno and Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, as well as others who would go on to produce Evangelion, participated in this production as its main staff.

(Image from Amazon.co.jp – Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise)

So, when you create a worldview from scratch to serve as your foundation, you go as far as to account for questions like, “How do these people live?” “What do they eat?” or “What do their toilets look like?” Of course, we don’t actually show what the Caninu use for toilets in our games, but because we have thought that in depth, when we go to present these characters in this fictional world, our worldview becomes that much more believable. And one title that we use as our standard has been Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise.

For more common worlds, like with the setting for .hack, we undergo much of the same. However, with a kemono-type world, we obviously aren’t kemono ourselves, and so we need to imagine and consider what would work as a solid foundation. We locate those elements and build from there, so it’s a bit more fun to think up a kemono-type world when you put it that way (laughs).

Itagaki:

The same goes for me as well. It’s quite fun to try finding a balance that my readers can be satisfied with.

Matsuyama:

It is, isn’t it? But that Black Market in BEASTARS was pretty crazy, I think! (laughs) The first time it made its appearance, it really blew me away, like, “Wow, you’re really doing both sides of the coin. This is nuts!”

We would like to try something like what you’ve done with the Black Market in BEASTARS, but games are far more regulated than manga are, especially in places like China.

With games these days, we have to design them with the premise that there will be regulations put in place on our visual depictions on a world-wide scale, and so a setting with places like the “underground” being included is hard to get people to let us do.

It would be a lot easier if we were to limit our [target] range and say, “this will only sell in Japan.” However, the moment we do that, then we’ll be shooting ourselves in the proverbial foot sales wise, and so from a business standpoint the only plausible thing for us to do is to approach our depictions differently.

――In that sense, manga have a bit more expressive freedom, don’t they?

Matsuyama:

Japan is clearly the “major leagues” for the manga market, wouldn’t you say? Sure, there are publishers overseas as well, but in all honesty overseas manga sales tend to be minuscule, with the majority of overall sales coming from within Japan itself.

Manga culture is a part of Japanese culture, and while we’ve seen some growth with webtoons coming out of Korea and China, the difference in our businesses is as stark as the difference between console gaming and social-network gaming.

Both BEASTARS and SANDA were drawn in analog.

――This is for Itagaki-sensei. Do you feel any certain changes within the entertainment world recently?

Itagaki:

Well, I’m an extremely old-fashioned artist, myself. My drafting thus far has all been done in analog format, with my penning and shading work being all done by hand.

I often get asked about that in interviews, but all I’ve been doing is sticking with the techniques that I started with. It wasn’t that I was stuck in my ways or anything—it’s just how things turned out. Despite that though, people have been referring to me as a “full-analog manga artist,” and so lately I’ve been wondering if I should stick with this method now (laughs).

Matsuyama:

You’re definitely a rare case, for sure. There are 2 different types of digital artistry as well: you’re either a full-digital artist, or you do your drafting and penning in the analog style, and from that point on it’s all digital.

Itagaki:

We have had the coronavirus, and since the standard globally is shifting more towards working from home, then I think maybe I should make the shift myself. That’s what I keep thinking to myself, but in practice I still enjoy doing things by hand. That being said, there is some frustration and internal struggle regarding not being “caught up with the times,” as it were. On the other hand, I do have the fun of being able to do original art exhibitions.

Matsuyama:

With analog you have the plus of being able to do exhibitions, don’t you? I love fresh manga manuscripts, so I often attend a number of different exhibitions from various artists. There’s nothing like the intensity of seeing the original thing in person.

Itagaki:

I know, right? You would think that readers wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between analog and digital when printed in magazines, but they really can, to my surprise.

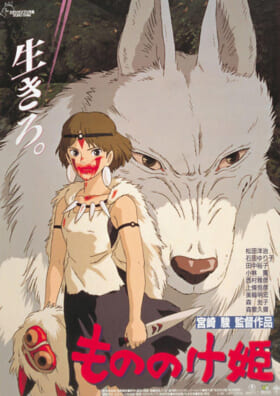

Out of Studio Ghibli’s anime, my hands-down favorite would be Princess Mononoke. I remember thinking back after watching Spirited Away, that something was somehow changed or different, if ever so slightly. Well, I looked into it and it turns out that the latter film is where they began introducing digital artwork. That’s when I thought that there must be some intrinsic value behind continuing with analog-type artistry, because there are people who get it.

(Image from Studio Ghibli – Princess Mononoke, Studio Ghibli – Spirited Away)

Matsuyama:

There are only a handful of analog-type artists with Weekly Shonen Champion, right?

Editor:

That’s correct. Out of those actively having their work serialized, Paru-sensei is one of three analog-type artists.

Itagaki:

One of three? There’s me, Yowamushi Pedal author Wataru Watanabe-sensei, and…

Editor:

Baki.

(Image from Amazon.co.jp – Yowamushi Pedal, Amazon.co.jp – Baki)

Itagaki:

Oh…right. (laughs)

Matsuyama:

Back in the day, all games used to be physical, but in recent years that has been changing. Honestly, digital games have a higher revenue yield rate, and games don’t degrade when they are in digital form, so it works out well for us there. But with manga, I would just buy both types.

Itagaki:

Really?

Matsuyama:

Yeah, I buy both paperback and digital.

Itagaki:

You’re the best kind of customer there is! (laughs)

Matsuyama:

Back then, I would take manga with me wherever I went. Carrying around 20 manga with you every day would be weird though, and so I’ve been reading digital copies when I’m on the move. When I’m at work though, I bundle up with a good physical copy to read.

|

Depending on the artist, there might be some that dislike digital, but all of Champion’s manga provide a digital version, correct?

Editor:

Yes, all of our artists’ works are being distributed in digital format as well.

Matsuyama:

I wonder if eventually all games and manga are going to be entirely digital. This happened to CDs long ago—there was just nowhere to put [physical copies]. When you move homes, you have to box them all up, and those things are heavy!

Itagaki:

Books are definitely the heaviest, aren’t they? I usually read my material in digital format, too.

Panel balancing in manga is also something that needs to be optimized to fit with the digital age.

Matsuyama:

This goes for SANDA & BEASTARS as well, but you can create intensity not just through words, but through artwork as well, right? Well, I think this includes a unique type of spacing [with panels]. Most female artists tend to use a more “shojo-manga” approach, as in they don’t do the typical shonen-style method of box-based paneling, but rather they often develop [stories] via their spacing. You’ve done more of the shonen-manga style though, Paru-sensei.

Itagaki:

Oh, really? I grew up learning the shojo-manga style, though.

Matsuyama:

You did!?

Itagaki:

I really liked shojo manga, but I also preferred the paneling style from bandes dessinée [*] stories, too, and so I often did combinations of the two. I personally thought that the beginning of BEASTARS in particular had some more unique paneling.

France and Belgium. Content in this format ranges from children’s tales, as seen in The

Adventures of Tintin, to more adult-themed works performed by skilled artists, including

Mevius and Enki Bilal.

(Image from TINTIN – Japanese Official Website)

Matsuyama:

True, the first part is as you say, but the middle portion of the story also has some shonen-manga qualities in the way the panels are organized and how the names are structured. The balance isn’t too dense—one of the positive qualities that shonen manga share.

Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball was easy for kids to read because its black and white color balancing was superb. I think your approach is slightly different though, Paru-sensei. In SANDA, you’ve got a distinct balance between lighting and shading, and I really think it’s easy to read as a shonen manga.

Itagaki:

I’m glad to hear it.

Matsuyama:

There are a ton of young artists these days that put so much effort into their artwork. Having a denser amount of information still makes it readable when on paper, but the minute you go digital, suddenly that information feels excessive, making it harder to read at times. But you’ve managed to set up your manga to be optimized for both physical and digital versions, and it’s simply fantastic.

Itagaki:

I’ve never been told that before. That makes me very happy to hear.

Matsuyama:

We’re creating our own “at-work” manga called Chaser Game, which sets the game development industry as the center stage for its plot. A personal rule that I have is to have a maximum of 5 panels per page, organized in no more than 3 rows or sections. The standard is that we must not reach 4 rows of panels.

Smartphones are the smallest device that we can currently read manga with, and so if we exceed that standard we’ve set, then we’ll have far too much information on one page, which will in turn force our readers to enlarge the page just to read it. That would just cause frustration for the reader to have to do.

I think it was probably Hell’s Paradise: Jigokuraku [*] from Shonen Jump+ that optimized font sizes within speech bubbles. At first it was different, but somewhere down the line they changed to a maximum of 5 panels and 3 rows, and when they did that, they could only fit about 3 lines of text in speech bubbles. On the other hand, though, they could increase the size of the font, and now it’s so much easier to read.

A Yuji Kaku shonen manga, released in serialized format on Shonen Jump+, the online Comic website. The story follows Gabimaru, a ninja who was once betrayed by his comrades and subsequently captured, as he puts his life on the line in his search for the Elixir of Immortality.

(Image from Hell’s Paradise: Jigokuraku – Japanese Official Website)

Itagaki:

I was actually very bad at drawing when I was little, and my pictures never fit onto the paper quite right (laughs). That’s how I was back then, and so even with manga to this day I tend to draw some fairly large images as opposed to smaller, more detailed ones, I think.

Oh, and I actually didn’t really read much of the ONE PIECE era of Jump Comics, either. It wasn’t until recently when I decided that I would finally sit down and read them.

Matsuyama:

What!? You didn’t??

Itagaki:

That’s probably why I didn’t read much of the more recent manga containing those smaller, more detailed panels.

There is always that one moment where the world of “kemono” just clicks with you.

Matsuyama:

By the way, do you regularly play video games, Paru-sensei?

Itagaki:

I don’t really play them that much, but I did start playing Monster Hunter recently so that I could bond with our assistant staff more.

Matsuyama:

Which means you’re probably playing Monster Hunter Rise for the Switch then, correct?

Itagaki:

Yes. I was so surprised at how well I’ve been playing. The other staff have been telling me that Monster Hunter basically has all the core elements of a game in it, and that “if you’re good at Monster Hunter, then you’re a pretty respectable gamer.” I’m pretty happy about that! (laughs)

Matsuyama:

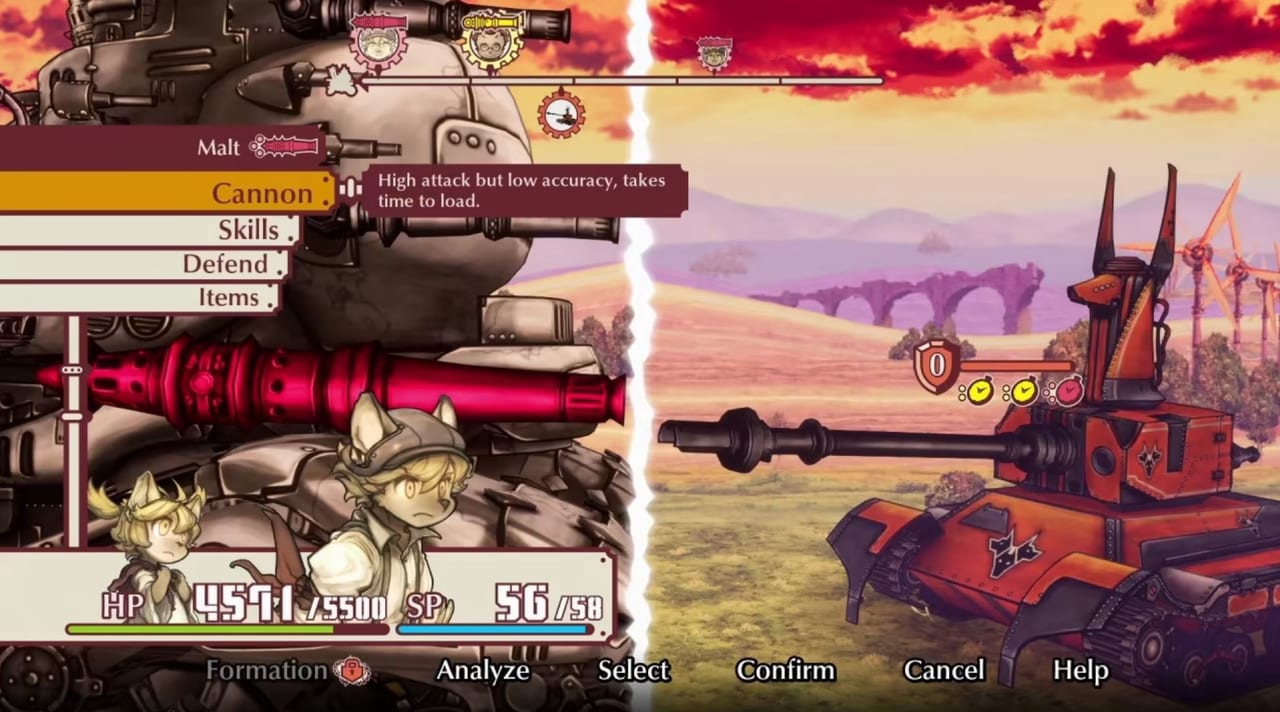

I understand you’re a busy person, but if you have the chance then by all means, please give Fuga: Melodies of Steel a try.

Itagaki:

I took a look at some documentation on it, and it has definitely piqued my interest. I would be happy to play it.

――That reminds me, you recently announced an upcoming comic adaptation of Fuga: Melodies of Steel, didn’t you?

Matsuyama:

Oh yes, that is in the good care of manga artist Takafumi Adachi, the one who created the comic adaptation for Beyblade: Metal Fusion. He’s quite fond of video games, and likes drawing kemono to boot. We sensed a connection there almost immediately, and he’s already proceeding with production as we speak. We think we’ll be able to put out an official announcement and release the manga in the near future.

We also have some other manga projects aside from Chaser Game and the Fuga: Melodies of Steel adaptation that are progressing behind closed doors, as it were. These aren’t manga that we wish to adapt into games later on or anything. Actually, we’ve been hoping to try our hand with some solid, standalone manga, too.

Our main focus is to create video games, but I also have a manga team working directly under me who are really trying to create interesting manga that can shake things up. On that note, we have no intention of creating any enemies here! (laughs) It’s just some good, friendly competition.

――How was the reception for Fuga: Melodies of Steel?

Matsuyama:

Thanks to our team we managed to release the game roughly three weeks ago (as of this interview), and we have been receiving great reviews.

I think that BEASTARS fits this perfectly, but there’s always that one moment when the world of “kemono” just clicks with you, and we want to be the standard for games with kemono-based worlds.

Pixar and Disney will periodically put out products that use “kemono” as their motif as well, but unfortunately their sales pale in comparison to their human counterparts, so I think that people tend to gravitate more towards the latter in the end. For adults, one look at a kemono-type character and they are convinced that it’s “for little kids.” This makes our audience count substantially smaller, I think. Still, Mickey Mouse’s motif is that of an animal, and so we want to hold fast onto our beliefs as we move forward.

Also, and I think a lot of this was influenced by BEASTARS, but in the past 5 to 10 years we’ve been hearing the outcry, especially from the U.S., louder and louder from those who would call themselves “furries.”

Itagaki:

I know what you mean.

Matsuyama:

Back then, whenever we put out a game, most of them would just keep quiet, and so that positive reception wouldn’t ever really get conveyed to us. Lately though, people have been much more vocal before and after release, especially in the U.S. We’re actually really grateful for that.

Itagaki:

The moment the BEASTARS anime released overseas on Netflix, we received this deluge of messages from all over (laughs). Our Twitter follower count suddenly skyrocketed, too.

――Which region gave the biggest response, would you say?

Itagaki:

I would say the U.S. and Europe has had a bigger response than that of the Asian region.

Matsuyama:

The U.S., France, Germany, and other areas nearby have all displayed a great deal of awareness [towards Fuga].

Editor:

France has seen the biggest response, followed by the U.S., and actually China as well.

Matsuyama:

The market in China sure is massive, after all.

Editor:

The response for SANDA has been extremely good, too. It feels like China is sorely lacking in options for entertainment these days.

Matsuyama:

Right now the top sales region for Fuga: Melodies of Steel is the U.S., but actually China is a close second place. Following that is Japan in third, and Taiwan under that. Europe doesn’t seem to be too enthusiastic just yet. What’s wrong, Paris!? (laughs)

|

China was a bit unexpected though! I think there might just be a kemono community growing there. Regardless, our aim is simply to increase sales for Fuga: Melodies of Steel. We’ll do our best to be as big as BEASTARS! (laughs)

Itagaki:

You’re such a kidder! (laughs) I had a lot of fun today.

――Thank you very much for joining us today. (END)

Afterword

Denfaminicogamer is currently working with former Weekly Shonen Jump editor-in-chief Kazuhiko Torishima on a series of articles about manga editors. For the first installment (only in Japanese text) we asked Torishima about the characteristics of major weekly manga publications, and he talked about Weekly Shonen Champion in particular.

According to Torishima, manga serialized in the Champion magazine are basically published in a one-shot format to discover new talent.

As Itagaki’s BEASTARS was a continuous story, it doesn’t appear to fall under this category, yet it also embodies that very characteristic with what she said in the above interview: “[…] the goal is for readers to continue to enjoy reading week in and week out.” According to her, this was also the thought process of Weekly Shonen Champion’s editor-in-chief for 11 years, Takafumi Sawa. In this way it’s evident that the Champion tradition has been continuously passed down to up-and-coming manga artists like Itagaki.

Itagaki also says, “By sticking to your own point of view, you can create a style entirely unique from others,” which is in line with the modern indie-game philosophy within the gaming industry. As CyberConnect2 is a game development company with a number of popular character-driven titles under its belt, Fuga: Melodies of Steel might not be considered an indie game in the strictest sense of the word. However, CC2 has dared to take up the path of in-house publishing to dedicate themselves in keeping the spirit of the Little Tail Bronx animal world alive. Just like Itagaki’s work, we look forward to shedding light on the kemono world by having more people get to know Fuga: Melodies of Steel, a title created under the watchful eye of Hiroshi Matsuyama with a focus on its unique individuality.